History is not a passive recollection of the past; it is a force that shapes the present and determines the future. Senegal, a nation once at the heart of France’s colonial empire, is now leading the movement to reclaim its sovereignty and reject the lingering grip of colonialism. Under the leadership of President Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal is undergoing a radical transformation. Renaming streets, rewriting textbooks, cutting military ties with France, and challenging foreign economic control.

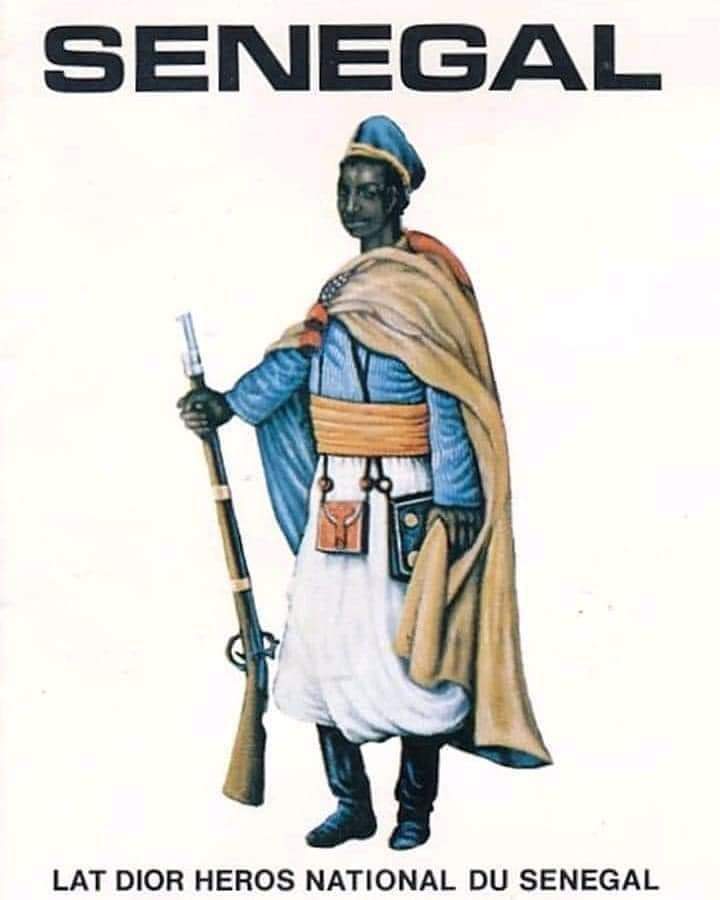

At the centre of this revolution stands Lat Dior Ngoné Latyr Diop, the legendary warrior-king of Cayor, who waged an unrelenting struggle against French imperialism in the 19th century. His fight, which cost him his life, was not just against military occupation but against the complete erasure of Senegalese sovereignty and identity. Today, as Senegal honours Lat Dior with a monument in his name, his spirit of resistance is being revived in a new generation of Senegalese leaders who are refusing to be pawns in the hands of Western powers.

But this is not just Senegal’s fight. Across West and Central Africa, former French colonies are rising up against the remnants of Francafrique, the system of French control that has long dictated economic and political affairs in its former colonies. From Mali to Burkina Faso, Niger to Chad, African nations are reclaiming their independence in a way that directly aligns with Frantz Fanon’s theory of decolonisation.

Lat Dior: The Warrior King Who Defied France.

Born in 1842 in Keur Amadou Yalla, Lat Dior was a ruler and the embodiment of Senegalese resistance against French colonial expansion. As the leader of Cayor, he refused to bow to European encroachment and fiercely opposed the construction of the Dakar-Saint Louis railway, which he recognised as a tool of colonial domination.

He understood that infrastructure projects like these were not intended for the benefit of Africans but were designed to facilitate the extraction of resources, consolidate military power, and entrench French rule.

Lat Dior’s resistance was political but deeply spiritual. As a devout Muslim, he built alliances with influential religious figures like El Hadj Oumar Tall and Ahmadou Bamba, believing that the fight for sovereignty was as much about cultural and spiritual liberation as it was about military struggle. His defiance made him a direct target of the French, and in 1886, he was assassinated by colonial forces. Yet, his death did not mark the end of the struggle—it became a rallying cry for future generations who continued to resist European rule.

In December 2024, President Faye honoured Lat Dior’s legacy by inaugurating a statue in his name, declaring that history is not merely something to be remembered but a guide for shaping a new Senegal. This act was about commemorating the past and a clear political statement. By restoring Lat Dior’s place in national memory, Senegal is rejecting the colonial narratives that once sought to erase him.

The Fall of Francafrique—Senegal and the Revolt Against Neocolonialism.

For decades, France has maintained an iron grip over its former African colonies through Francafrique, a system of political, economic, and military control that kept African nations dependent and subservient. Even after so-called independence, France retained strategic military bases, controlled natural resources, and imposed economic policies that prioritised its own interests over those of the African people.

But that era is coming to an end. Senegal has now joined a wave of nations that are rejecting French domination. In 2024, President Faye called for the withdrawal of French troops from Senegal, following in the footsteps of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, all of whom have expelled French military forces in recent years.

This was a diplomatic move and a declaration of true sovereignty. The timing was deliberate, on the 80th anniversary of the Thiaroye massacre, when French colonial forces slaughtered West African soldiers who had fought for France in World War II, Senegal made it clear that it would no longer tolerate foreign military occupation.This is a reflection of the growing consciousness among African citizens who refuse to accept neocolonial control any longer.

Senegal as a Case Study in Fanon’s Theory.

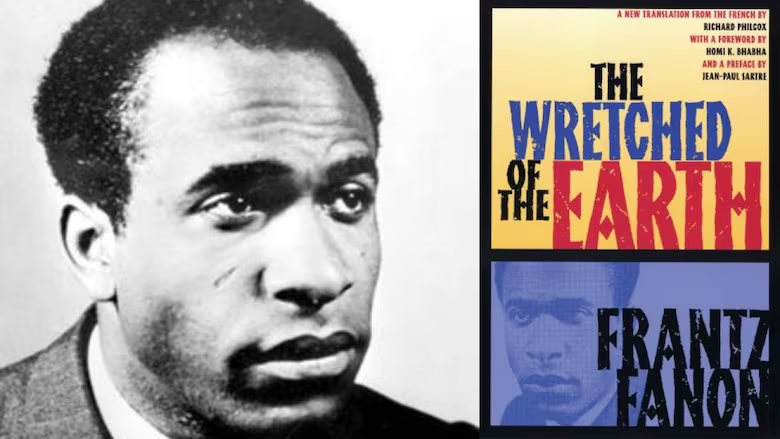

Frantz Fanon, in The Wretched of the Earth, articulated the psychological and structural dimensions of decolonisation.

He argued that true liberation requires not just political independence but the complete rejection of colonial values and the construction of an entirely new national consciousness. Senegal’s decolonial movement is a direct embodiment of Fanon’s philosophy.

Fanon warned against the dangers of colonial assimilation, where the colonised internalise the values of their oppressors and continue to function within a system that was never designed to serve them.

Senegal’s efforts to remove French names from public spaces, rewrite history textbooks, and celebrate African resistance figures represent a rejection of European narratives. This is the beginning of a new historical consciousness, one that is written by and for Africans.

Fanon also stressed the importance of unity among the colonised. Senegal’s actions are not occurring in isolation but as part of a broader Pan-African movement that is sweeping across Francophone Africa. By standing in solidarity with Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, Senegal is reinforcing Fanon’s argument that decolonisation cannot be a nationalistic struggle alone; it must be a collective, continental movement against imperialism.

Most importantly, Fanon believed that decolonisation was about restoring the dignity of the colonised. For too long, African nations have been made to believe that they cannot survive without the guidance of Western powers. By cutting military ties, questioning the CFA franc, and demanding reparations for colonial atrocities, Senegal is rejecting this falsehood. It is asserting that Africa does not need Europe to determine its destiny.

The Next Step: Economic Liberation.

Fanon was clear: political independence without economic autonomy is meaningless. Colonialism did not end with the departure of European administrators—it evolved into economic control, where African nations remained trapped in a system that prioritised Western profits over African development.

Senegal is now taking the first steps toward breaking free from economic neocolonialism. President Faye’s administration has raised the question of the CFA franc, a currency controlled by France that continues to dictate monetary policy in 14 African nations. While full departure from this system has yet to be realised, the conversation itself is significant. The government is also reviewing foreign business contracts to ensure that Senegal’s resources benefit its people rather than multinational corporations.

The road to full economic sovereignty will not be easy. Western institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF continue to exert control over African economies through debt and structural adjustment programs. But Senegal’s willingness to challenge the status quo is a step in the right direction. It is a reminder that decolonisation is not a single event but an ongoing process of dismantling all structures of oppression.

The Future is Decolonised

Fanon warned us that the fight against colonialism would not end with independence declarations. The real struggle is in ensuring that African nations do not become mere extensions of their former colonisers. Senegal is proving that decolonisation is a living revolution. The question now is, WHO IS NEXT?