Sickle cell disorder distorts red blood cells into a “sickle” shape, making them clump in vessels and cause painful crises. This inherited condition was first recognised in the UK in the 1950s, just as waves of post-colonial migrants arrived and the NHS expanded. In that era, many white Britons refused to acknowledge it as a “British” illness. The history of SCD care in Britain is deeply entwined with Empire and racism; a story of migrants bringing the disease to the health service, only to have their suffering dismissed.

Early NHS doctors and the media often mischaracterised sickle cell. Migrants from Africa and the Caribbean were expected to be staff, not patients, and some newspapers blamed them for “bringing” SCD to Britain. Racist myths spread; for example, MPs even raised the question of banning black blood donors over “risk” of sickle cell.

In the 1950s–60s the far-right press fuelled fear that SCD was infectious and tied to race. Black nurses were even scapegoated, accused of passing sickle cell to patients. Many people with SCD in the 1960s were too afraid to tell friends or family about their illness. Black nursing staff in the NHS remember feeling powerless and sidelined against rigid hierarchies. Training on genetic counselling and sickle cell simply did not exist. This structural racism meant patients often received no official support while white doctors and officials looked the other way.

For decades sickle cell sufferers in Britain were treated as second-class patients. Doctors saw it as a “niche” condition and told Black patients in agony that they were drug addicts. A modern report notes that many people with SCD are still denied pain relief in hospital; staff too often assume “as a Black person, they are simply drug seeking”. The 2021 No One’s Listening inquiry by MPs found “serious care failings” in A&E departments, a widespread lack of sickle cell knowledge, and frequent reports that negative attitudes toward sickle patients were underpinned by racism. Deep racial bias persists: SCD patients “report being treated with disrespect, not being believed or listened to” when in crisis. In short, structural racism and ignorance in the NHS have long compounded the physical suffering of sickle cell.

Key issues in sickle cell care today include:

- Very limited treatments: only two NHS-approved drugs for SCD (versus five in the US).

- Far too few specialist staff: about 0.5 specialist SCD nurses per 100 patients, compared to 2 per 100 for cystic fibrosis.

- Major funding gaps: research funding for cystic fibrosis is roughly 2.5 times higher than for sickle cell.

- A postcode lottery: emergency and specialist SCD services are concentrated in a few areas (mainly London/Manchester), so getting good care still “predominantly comes down to the prevalence of the disorder in your area”.

These disparities are symptoms of institutional neglect. Data from the NHS Race & Health Observatory (June 2025) confirms that people with sickle cell face stark inequities in care, research and treatment compared to other conditions like haemophilia or cystic fibrosis. For example, UK hospitalisations for pain crises are the highest in any country studied and many patients still prefer to manage pain at home after negative experiences. Sickle cell is now one of England’s fastest-growing genetic conditions, about 250 new cases a year, yet awareness and resources remain far behind need. Unless these systemic injustices are addressed, the same old patterns of neglect will continue.

Support has long come from within the Black community itself. Black pioneers laid the groundwork for today’s services.

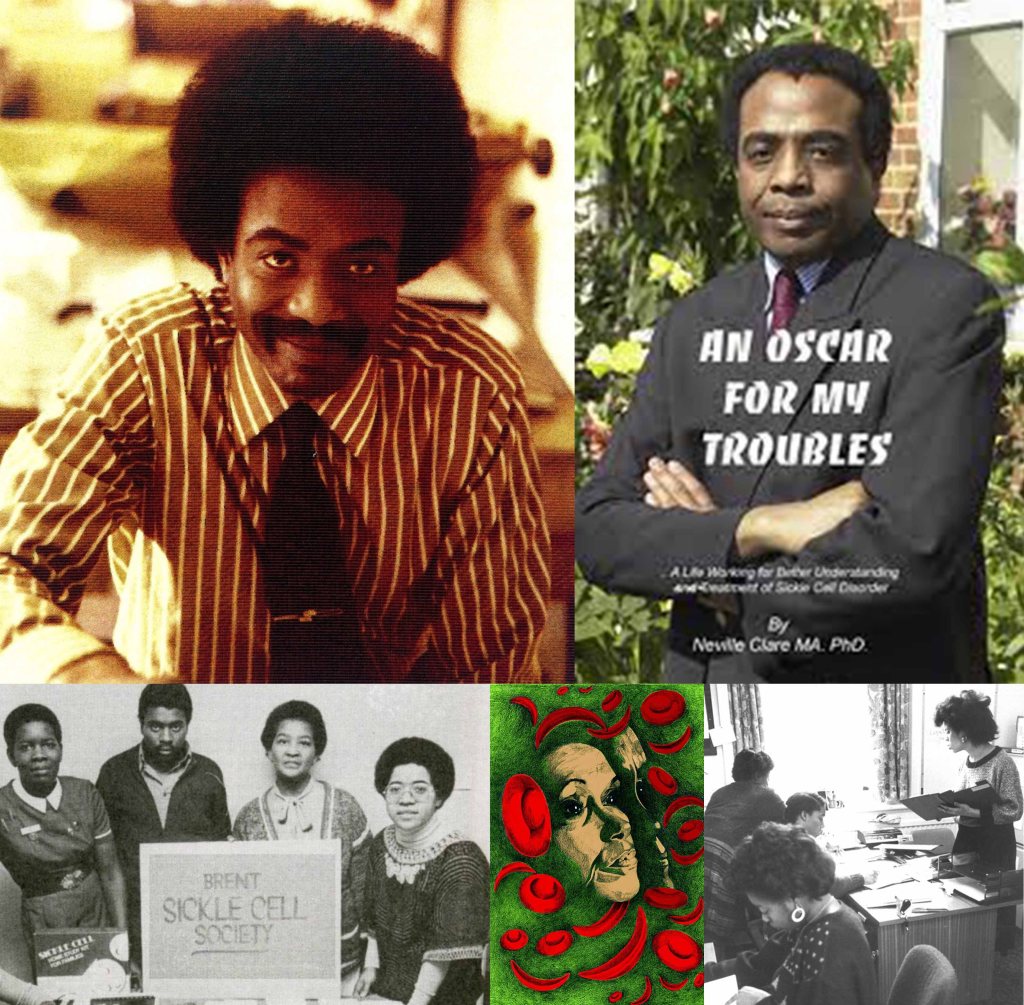

Dr Neville Roy Clare (1946–2015), born in Jamaica but raised in London and he was diagnosed with sickle cell as a child, refused to stay silent about the disease.

In 1975 he founded OSCAR (Organisation for Sickle Cell Anaemia Research), the UK’s first sickle cell charity. OSCAR provided medical advice, education and community support where the NHS had none. His grassroots activism became a template for all later UK and European SCD support groups.

Likewise, Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu (born 1947) broke new ground.

In 1979 she became the UK’s first sickle-cell nurse specialist and co-founded the Brent Sickle Cell Centre. Anionwu later trained generations of nurses in culturally sensitive genetic counselling. Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu devoted her careers to better care and to challenging racism in medicine.

This legacy reminds us why Sickle Cell Awareness Month is so important. Each September offers a chance to honour these trailblazers and to educate the public and health service about sickle cell. Awareness campaigns spotlight the ongoing inequities: for example, by noting the lack of treatments and specialist staff mentioned above, and by calling out the “postcode lottery” in access to care.

During Sickle Cell Awareness Month, BLAM UK and allied organisations urge the NHS to act on these facts. The history is clear: Empire and institutional racism shaped sickle cell neglect. We know how to fix it! through proper funding, specialist training, and community-informed care.

Awareness month is a time for the Black British community to share knowledge, honour the work of Dr Neville, Dame Anionwu and others, and demand change. By centring Black voices and scholarship, we challenge old prejudices. In the words of the 2021 inquiry, we must ensure “no one’s listening” becomes “everyone’s responsibility” – so that people with sickle cell finally get the equal, compassionate care they deserve.

Further reading: : Empire, Racism and the NHS: Why Sickle Cell Awareness Month Matters?- Grace Redhead, “Empire, racism and the NHS: the history of sickle cell disorder,” RCN History (Nov 2022).

- APPG on Sickle Cell & Thalassaemia, “No One’s Listening: A Report” (Sickle Cell Society, 2021).

- NHS Race & Health Observatory, “Sickle Cell: Comparative Review to Inform Policy” (June 2025).

- C.J. Nwasike, “The implicit bias of sickle cell disease,” King’s Fund blog (June 2025).

- Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu, Mixed Blessings from a Cambridge Union (memoirs, 2016).