International Migrants Day prompts us to reflect on our own stories. For Black Brits, whether from the Afro-Caribbean or African diasporas, migration isn’t just a distant concept, it is family history. Our parents, grandparents, and communities often arrived as migrants, helping build this country.

On this day we recall those journeys and the truths they teach us. Thinkers like Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy help explain how Black identity is forged in motion and exchange. We also confront today’s politics: from the Prime Minister’s warning of an “island of strangers” to Nigel Farage and Tommy Robinson’s “great replacement” myths. By centering Black British voices, from academics to artists, we reclaim the migrant narrative.

Remembering Our Migrant Roots

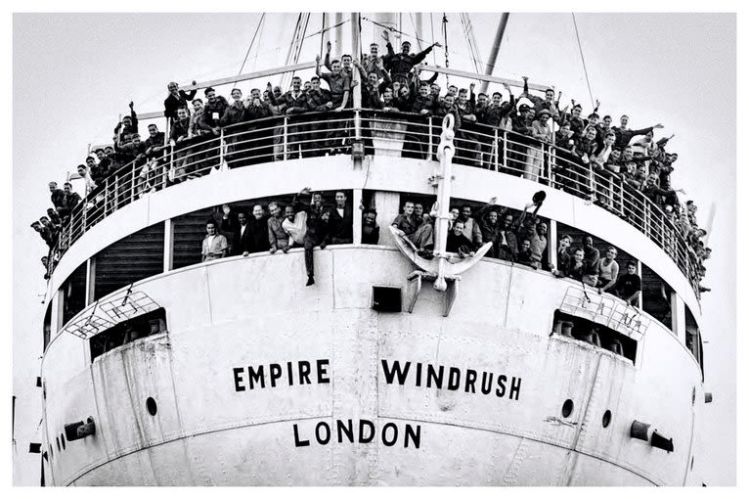

We must honor the very real contributions of Black migrants to Britain’s story. The post-war Windrush generation is emblematic: on 22 June 1948, 400+ Jamaicans arrived on the HMT Empire Windrush to answer Britain’s call to help rebuild the economy and new NHS.

Within days, many had jobs; by 1958 roughly 125,000 West Indians (and tens of thousands from India and Pakistan) had come to work here. Black migrants filled crucial roles in public life. For example, by 1971 about 31% of NHS doctors in England were born and educated abroad. Caribbean nurses and African doctors ran wards that few Britons wanted. These dedicated pioneers did the work that kept schools, hospitals and businesses running, even as they faced racism at home.

- Post-war pioneers: More than 400 Caribbean migrants on the Empire Windrush arrived in 1948 to help rebuild Britain, especially the fledgling NHS. Many West Indian women became nurses, often working “immaculately starched” in British hospitals as their descendants proudly remember.

- Vital workers: By the late 1960s, foreign-trained staff were everywhere. In 1971, nearly one-third of English NHS doctors were educated overseas. Migrant porters, cleaners and cooks kept schools and hospitals open. Without them, as advocates note, “the history of the NHS is also the history of migration”.

- Building communities: Caribbean and African migrants founded businesses, churches, Carnival celebrations, sports clubs and more. They raised generations of British-born children who are simultaneously proud Londoners and proud of their heritage.

These facts show that migrants, our communities included, made Britain work. Remembering this history challenges any claim that we “don’t belong” here.

Black British scholars have long explored what it means to live between worlds.

He described cultural identity as a process, not a fixed label. Hall argued that beneath surface differences there is a shared Caribbean and African legacy, a sort of collective one true self, that each diaspora member must discover, excavate.

In his writings on Black popular culture, Hall even noted that people of the Black diaspora have “found the deep form, the deep structure of their cultural life in music” – capturing how art and culture keep our stories alive. In short, Hall’s life and work embodied how migration and colonial history shape identity.

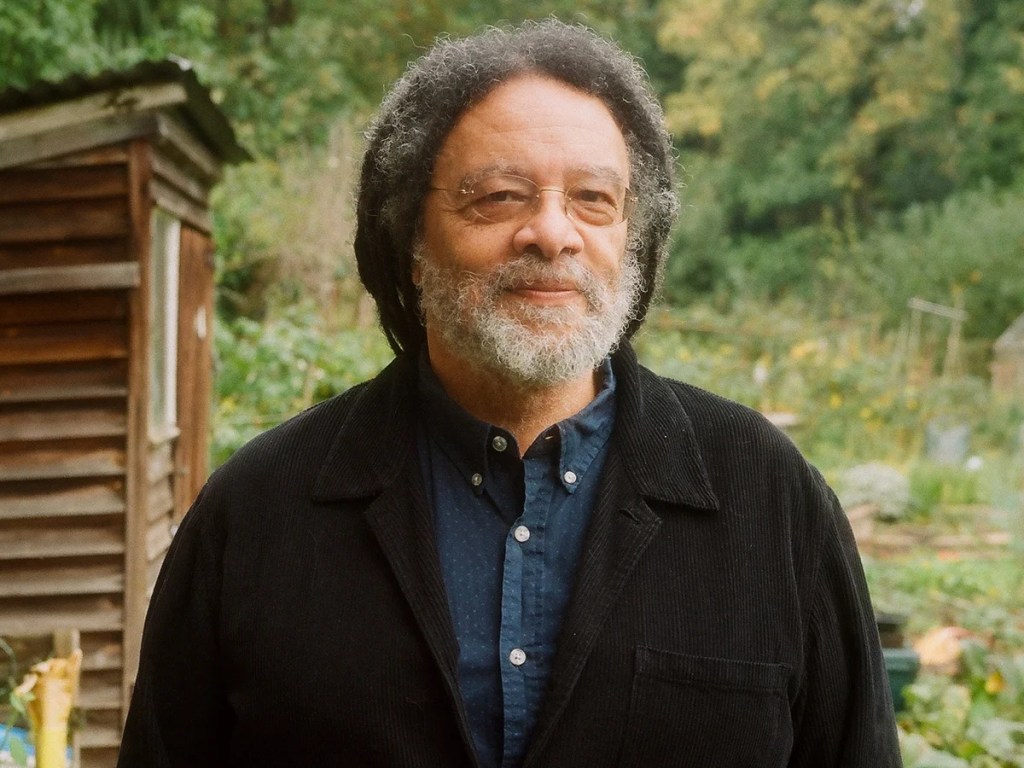

Paul Gilroy (London-born scholar of the African Diaspora) builds on this. In The Black Atlantic, Gilroy argues Black identity in Britain, the US and the Caribbean is inherently transnational.

He shows that over 150 years Black intellectuals and artists have “traveled and worked in a transnational frame” – thinking and creating across oceans, rather than being rooted in one nation. Gilroy’s “Black Atlantic” model reminds us that African and Caribbean cultures cross borders. We carry those voyages in us: our music, stories and politics connect to global Black history, not just to Britain.

Kehinde Andrews (Birmingham-born academic and activist) adds a modern perspective. As Britain’s first professor of Black Studies, he urges the diaspora to unite globally.

Andrews insists that, “as Black and African people, our true power… is in organizing ourselves globally”. In other words, Black Britons benefit by seeing ourselves as part of a wider struggle with Africans and the world’s Black communities, not just as an isolated group.

He also speaks frankly about our relation to Britain. For many of us, as he notes, “racism is as British as a cup of tea, which is why so many of us reject both the nation and the monarchy”. This blunt truth reminds us that Black Britons often view Britain’s national myths differently, understanding that the country’s wealth came from colonialism and slavery.

These thinkers teach us: our identities are complex and creative, forged across journeys. They encourage pride in diaspora roots and solidarity with other Black people globally.

Confronting Fear: Debunking the “Island of Strangers”

Last year even the Labour leader warned that the UK might become an “island of strangers” – echoing Enoch Powell’s infamous 1968 trope. But Black voices push back strongly. As one British-letter-writer put it: “Immigration doesn’t lead to an ‘island of strangers’, rather to a diverse, modern nation. The UK shapes immigrants, and in turn this country is shaped by immigrants and their descendants.”. Indeed, diversity is our reality and strength. Rather than division, migration has remade Britain’s identity again and again, making it a more modern, global nation.

On the far right, figures like Nigel Farage and Tommy Robinson peddle conspiracies like the “Great Replacement” – the idea that white Britons are being “replaced” by immigrants. But this is baseless. As a Guardian analysis notes, anti-immigrant fringe groups merge xenophobia with other agenda (such as anti-abortion) into claims that migrants “replac[e] white Brits”.

Even Tommy Robinson has promoted the same “great replacement” narrative. We must reject these scare tactics. We know from history (and from our own lives) that migrants and native-born people live and work side by side. Britain’s needs, from care workers to teachers, have long been met by immigrants, not hurt by them. In reality, warnings about being “submerged” or “invaded” are a political ploy to divide us.

Instead, we remember the real picture: our families, like one Chinese-Vietnamese family in London wrote in response to the “strangers” remark, not only became successful by running businesses and education, but loved being British. Diverse communities support each other: on one street neighbours of all backgrounds join together in celebrations and mutual aid, not isolation.

Culture and Identity: Our Stories in Art

Our perspective also comes through art and culture. British music has powerful stories of migration. For example, the rapper Dave (a British-Nigerian artist) released a song called “Black” that many of us found deeply personal. In it he declares “Black ain’t just a single fuckin’ colour, man – there’s shades to it”. Dave’s line reminds us that within Black identity there are many histories and backgrounds: Caribbean, African, mixed heritage, and more. The song even becomes a brief history lesson “West Africa, Benin, they called it slave coast”, highlighting how the Atlantic slave trade and colonisation still echo in our lives today.

Songs like Dave’s “Black” and other cultural works give voice to our collective memory. They celebrate that “Black is beautiful, Black is excellent” (as Dave also proclaims), while also calling out injustice: “A kid dies, the blacker the killer, the sweeter the news…” (another lyric) argues he, underscoring media bias. Listening to these artists, we feel seen: they echo Paul Gilroy’s idea that our shared histories travel through music, and Stuart Hall’s insight that diaspora cultures “play solos in tune and in contradiction” with Britain. When we hear our own stories in songs, literature or films, it affirms our place here and connects us to a larger Black creative legacy.

On this Migrants Day, we stand in solidarity with all migrants.

We remember that history offers undeniable evidence of the meaningful and enduring contributions made by migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. This is no abstract claim; it is our history. In fact, hundreds of UK organisations recently pledged themselves to unity, declaring Britain an “island of solidarity, not strangers”. Their statement explicitly affirms the inherent right to live in peace, dignity and hope of every migrant. We Black Brits endorse that pledge. We know every immigrant, our parents, grandparents and neighbours, has that right.

So on International Migrants Day we do more than observe; we remember our own journey. We think of the courage of ancestors who crossed oceans, and the pride of cousins, children and friends born here. We draw inspiration from Stuart Hall’s, Paul Gilroy’s and Kehinde Andrews’s ideas: they teach us that we belong in multiple worlds at once, and that our home is enriched by all those who come to it. We celebrate our culture, from steel drums to grime rap, that blends African, Caribbean and British elements. We reject divisive myths (Farage’s and Robinson’s) and instead pledge community support.

International Migrants Day is a reminder that migrants built this country, and that Black people are a central part of that story.