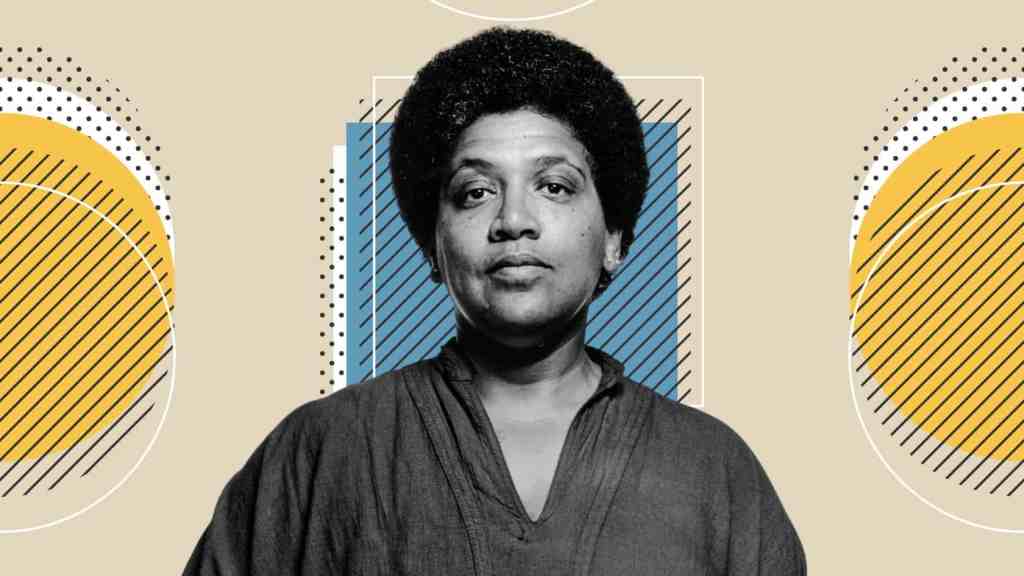

Audre Lorde in 1980. Audre Lorde was a Black, queer feminist poet and activist who transformed the way we understand identity, care, and resistance. Through her writings and speeches, Lorde urged marginalized people to prioritize self-care as an act of survival, asserting that nurturing one’s own well-being is not selfish – it’s a necessary weapon against oppression. As we mark Lorde’s birthday (February 18) during U.S. Black History Month, we celebrate how this “warrior poet” used radical self-care to empower herself and her community in the fight for justice.

A Warrior Poet in the Fight for Justice

Audre Lorde often introduced herself as a “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” signaling the many facets of her identity and struggle. Born in 1934 in Harlem to Caribbean immigrant parents, she came of age amidst racism and segregation. Lorde found her voice through poetry at a young age and later became a librarian and educator. By the 1960s she was deeply involved in activism – from the Civil Rights movement to the women’s liberation and gay rights movements. Her experiences as a Black queer woman in America fueled her demand for intersectionality in social justice: she insisted that the different parts of our identities (race, gender, sexuality, class) cannot be separated in the struggle for equality. Lorde’s activism was broad and global.

She spoke at the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights and co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1981 to publish works by Black feminists. She even helped build connections with activists in apartheid South Africa. Through all her work, Lorde was a fearless truth-teller, unafraid to call out racism in feminist spaces or homophobia in Black spaces. Her life’s mission was to empower those rendered voiceless by society – and to show that embracing one’s full, authentic self is a potent act of resistance.

Self-Care as Self-Preservation

One of Audre Lorde’s most enduring lessons is her redefinition of self-care. In 1988, while battling terminal cancer, Lorde wrote the now-famous words: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” At a time when Black women like herself were expected to be selfless caregivers or strong workhorses, Lorde turned that idea on its head. She declared that preserving her own health, sanity, and spirit was a political act – a way to refuse the destructive pressures of a racist, sexist society. For Lorde, self-care was not about pampering or consumer comforts. It was “the sustenance that sustained her ability to enact change”. As a Black queer woman, she knew that the society around her did not prioritize her well-being at all – so she had to prioritize it herself. Lorde likened her fight against oppression to her fight against cancer.

In both battles, survival required strength and vigilance. She warned against “overextending” oneself in activism, noting that burnout and exhaustion only serve the systems that want to silence oppressed voices. By caring for her body and mind, Lorde equipped herself to keep speaking out, writing, and fighting. She urged her peers to do the same, especially Black women who faced the double trauma of racism and sexism every day. This holistic view, that mental and physical health are part of the freedom struggle, was groundbreaking. It challenged the idea that activism must equal self-sacrifice, and instead proposed that self-preservation is a form of political resistance.

Legacy of a Radical Vision

Audre Lorde’s radical self-care philosophy resonates powerfully to this day. In recent years, we have seen a resurgence of her ideas in movements like Black Lives Matter and Black feminist organizing. Activists cite Lorde when reminding each other to rest and heal, knowing that rest is resistance and that we can’t pour from an empty cup. Especially for Black people, women of color, LGBTQ+ folks and others on the margins, Lorde’s words offer permission to care for ourselves in a world that often neglects or attacks us.

Her influence is evident in the modern discourse around “radical self-care” and “community care.” For example, wellness initiatives in activist communities and the rise of groups like The Nap Ministry (which advocates rest as reparations for Black people) draw directly from Lorde’s insight that caring for oneself is not a luxury.

Moreover, Lorde’s life exemplifies that self-care and community care go hand in hand. She fostered communities of support – whether through creating a publishing press for women of color or organizing healing circles for Black women with cancer (as she did in The Cancer Journals). By openly discussing her struggles – from racism to her health – she showed that sharing pain and caring for each other can dismantle the system that wants Black and brown people to “keep it all inside”. Today, scholars and activists credit Audre Lorde for this crucial reframing of self-care. What started as a deeply personal revelation – a Black lesbian poet listening to her body and spirit – became a rallying cry for collective survival. Lorde’s legacy teaches us that tending to ourselves is not selfish, it is self-preservation, and in her words, “better we learn to mother ourselves” than to capitulate to a world that would see us used up.

As we honor Audre Lorde on her birthday and during Black History Month, we are reminded that her voice is a guiding light. Lorde showed that the act of self-care is a radical declaration of worth – a way of saying that we deserve to thrive even in a system that aims to break us. Her life’s work, spanning poetry, essays, and activism, continues to inspire new generations to speak up, to embrace their identities fully, and to care fiercely for themselves and each other. In Lorde’s spirit, caring for ourselves is not about escaping the world’s problems; it is about equipping ourselves with the strength to change the world. This Black History Month, let Audre Lorde’s example ignite in us the courage to rest when weary, to love ourselves unapologetically, and to fight on for liberation – because our self-preservation is an act of political warfare