Kwanzaa: African American festivities and the search for a self-defined identity

Written By Maria Motunrayo

A media exposure to Kwanzaa occurred through an episode of Everybody Hates Chris. Chris’ father, Julius, introduces Kwanzaa as a cheaper alternative to Christmas under the disguise of prioritising the family’s African roots, and embracing the spirit of Umoja – unity in Swahili.

“Are you doing Kwanzaa cause it’s cheap?” Rochelle says, triggering the sitcom’s laughter track. This idea isn’t exactly incorrect. Elizabeth Pleck (2001) notes, “Kwanzaa drew much of its appeal from appearing to be the less commercial alternative to Christmas.” However, this is a gross simplification of what the festival signifies to African Americans. As a Nigerian-British woman who grew up wearing aso ebi to church on Sundays, watching African Americans wearing a blend of Ankara, Dashikis and Kente while saying americanised Swahili phrases held a great curiosity for me.

The way they spoke about Africa while celebrating Kwanzaa in Everybody Hates Chris, evoked this alien idea of a simple people that gave corn as presents (as Julius suggests to his daughter Tanya on the show), and also this equally foreign concept of a resplendent, Pan-African kingdom where a myriad of cultures blended into one, where everyone is a descendant of a King or Queen.

Chiefly this piece will examine the prevailing views regarding Kwanzaa – is Kwanzaa just a less capitalist Christmas that includes a delusional myth of an Africa that never existed? Or is it a powerful, self-defining ritual that can be celebrated by all members of the African diaspora?

Let’s start with the festival itself – Kwanzaa is a seven day affair that conveniently begins on December 26th, and lasts until the New Year. The date of Kwanzaa and the fact that it is the day after Christmas, is highly convenient. Kwanzaa was initially formed out of 1960s anti-Christian Black Nationalist sentiment, after all it was “created by an intellectual hostile to Christianity”, but it grew in popularity from the 1980s onwards when “it was seen as a supplement to Christmas” (Pleck 2001).

Most importantly, Kwanzaa can provide African Americans with what Christmas lacks – racial esteem. Traditional clothes are worn from several Black ethnic groups, mostly tribes in African countries that were particularly inspiring for Black Nationalists such as Marcus Garvey, who was a huge inspiration to the founder of Kwanzaa, Maulana Karanga. This is why African Americans celebrating the festival can be seen wearing traditional South African, Nigerian and Ethiopian wear. However, the language of Kwanzaa is Swahili, as Swahili was seen as the unifying language of Pan-Africa.

As Flores-Peña and Evanchuk (1997) note: “Kwanzaa is the only specifically African American festivity that has attracted a significant port of the African American population, which is increasingly looking for identity and meaning for its ethnicity.”

Kwanzaa takes place in the African-American family home where children are instructed by their parents to light the seven pronged candle that has black, red and green candles (the colours of Black Nationalism), while they reflect on a key principle (Nguzo Saba) for seven days. It is imperative that children explain the principles to their family after they learn them, as this helps build an understanding of their ethnic roots outside of the US.

On the last day, New Year’s Eve, a “Karamu” ( last-night feast) occurs where people outside the family including the local community are invited to partake in African meals, as well as southern food and Caribbean food and “African dancing and telling of African folk tales.” (Pleck 2001) In addition, at the Karamu everyone drinks from a unity cup and says, “Harambee” which means “all pull together” in swahili.

Harambee encompasses a Kenyan spirit of national unity and patriotism, it is so vital to their national consciousness, it even appears on their coat of arms. This is most likely why it is chosen as a Kwanzaa phrase by its founder, after all, Kwanzaa was intended to provide a sense of national identity for African Americans outside the US. Karenga says himself in 1988, that Kwanzaa helps African Americans “reconstruct their life in their own image and interest and build and sustain an Afrocentric family, community, and culture.” The Karamu also encompasses African American traditions including jazz, spoken word and poetry, and once the rites are done it is common for celebrants to “gig all night long” (Pleck 2001).

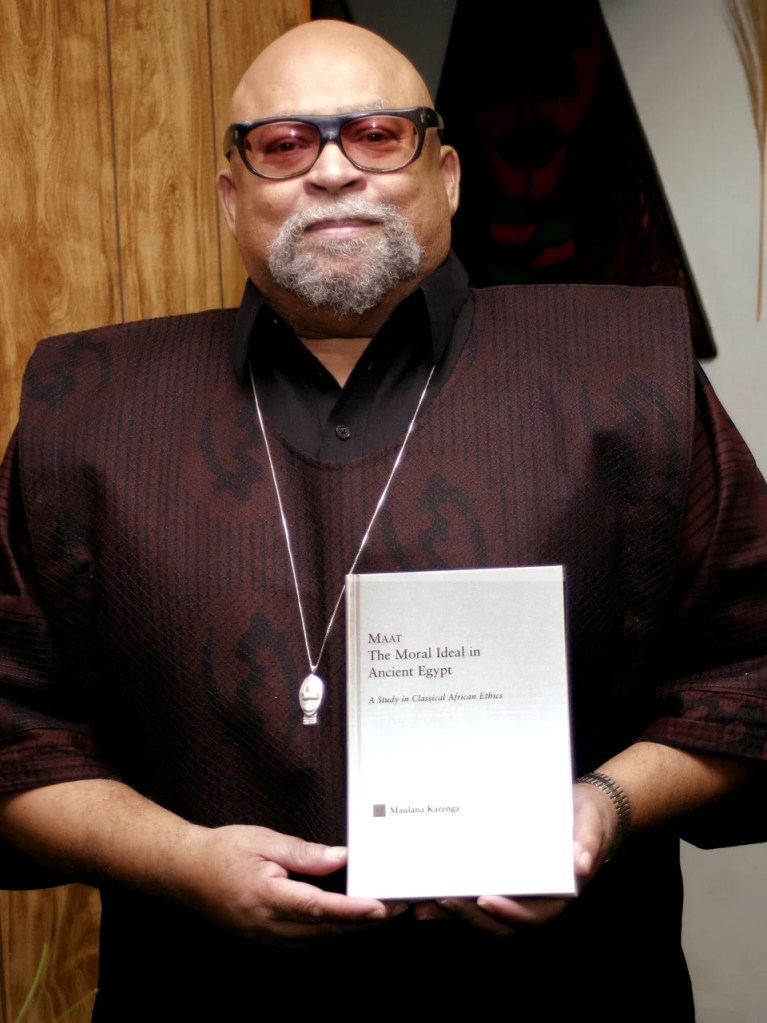

Founder Of Kwanzaa

The founder of Kwanzaa Maulana Ndabezitha Karenga, created the seven principles as a cultural response to the Watts 1965 riots. The riots stemmed from the anger caused by police brutality and inequality. They lasted five days and left 34 dead and 900 injured. Maulana Karunga insists that the seven principles of Kwanzaa, the Nguzo Saba, are taken directly from Africa. The implication is that once the principles are followed, they would prevent such events as the Watts riot. The principles are:

1. Umoja (unity)

2. Kujichangulia (self-determination)

3. Ujima (collective work and responsibility)

4. Ujamaa (cooperative economics)

5. Nia (purpose)

6. Kuumba (creativity)

7. Imani (faith)

Maulana insists on the fact that these are African principles especially curious, especially as at the time he created them, he had not been to any country in Africa. Maulana means “tradition” in swahili. The founder of Kwanzaa was actually born Roland Everett in 1941, one of fourteen children of a Baptist minister in Parsonsburg, Maryland, and a homemaker (Pleck 2001). The Seven principles are mostly entrepreneurial, and therefore, mirror the values that were important to the intellectual rising Black influential founder belonged to.

Karunga did draw from several cultures within the African diaspora to create Kwanzaa, however it is more indelibly imbued with African American revolutionary culture, more than anything else. However, the accuracy of the Kwanzaa rituals are not what is important, but the emphasis on practising rituals exclusively within the Black community. I believe it also provided some of the initial racial esteem training for Black children in the diaspora which has provided positive alternatives, mythical or not, on what it means to be Black. And without positive fuel for the Black consciousness, movements such as Afrofuturism, may not have been possible.