Hidden in the heart of Lagos Island lies a neighbourhood with a powerful story, a place known as the Brazilian Quarter, or Popo Aguda. What makes this area so unique is it’s legacy of a people who were kidnapped and taken across the Atlantic in chains, found freedom, and returned home carrying their memories, culture, identity, and pride.

From Enslavement to Return

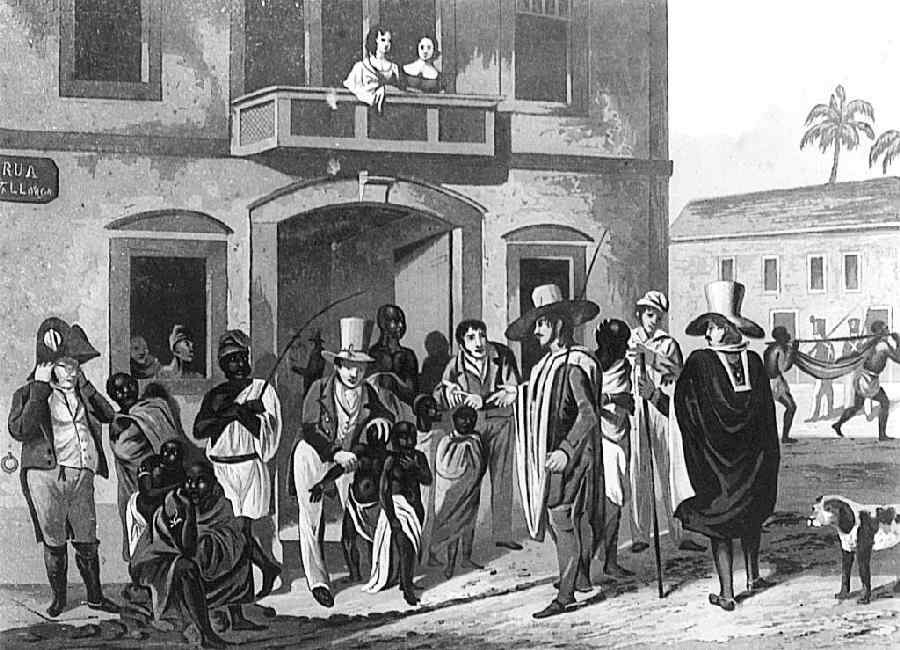

During the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, millions of Yoruba people were taken from what is now Nigeria and enslaved in Brazil. Despite facing brutality, they held tightly to their language, religion, and traditions. Cultural survival became an act of resistance.

In the late 1800s, after slavery was abolished in Brazil, many of the Yoruba who had been enslaved, known as Agudas or Emancipados, made the decision to return to Lagos. When they arrived, they brought back stories, skills, spirituality, and a strong sense of community.

Rebuilding Home with Culture.

The returnees didn’t just settle in Lagos, they helped shape it. They built homes and public spaces in the Portuguese-Brazilian style, using architectural techniques they learned in Brazil. From the arched windows and stuccoed walls to the iron balconies and detailed designs, these buildings became a statements, a declaration that the returnees were no longer enslaved and that they were home, and they were proud.

Today, you can still walk through the streets of Popo Aguda and see the legacy in the buildings. Places like the Holy Cross Cathedral and the Brazilian Salvador Mosque, built by these returnees, stand as symbols of unity; both in faith and identity.

Culture as Resistance

But architecture was just one piece of the puzzle. The returnees also revived and reshaped cultural traditions that have lasted for over a century. Festivals like Caretta and Meboi are still celebrated today, bringing people together across religions.

During Caretta, participants wear bright costumes and masks, dancing through the streets to music, laughter, and joy. Though it began as a Christian festival, it’s now open to everyone; Christians, Muslims, and traditionalists alike.

Meboi honours respected elders and involves parades with horse riders dressed in powerful, symbolic outfits. These celebrations are a reminder that even after centuries of separation, forced migration, and oppression, culture can still live on. In fact, culture becomes a weapon, not of violence, but of survival, strength, and healing.

Unity Through Heritage

The Brazilian Quarter is a beautiful example of how identity can be rebuilt. Despite facing religious differences, poverty, and marginalisation, the community remains united through shared history. Everyone eats the same traditional foods like Frejon on Good Friday. Everyone joins in the street celebrations. Everyone belongs.

The people of Popo Aguda continue to honour their ancestors through their language, clothing, food, and names; many still bearing Brazilian surnames like Da Silva, Martinez, Pedro, and Damazio. In doing so, they preserve a living memory of what their forebears endured and overcame.

A Legacy That Lives On

In recent years, the Brazilian Embassy has recognised the importance of this cultural connection, offering support and even planning to provide Portuguese language lessons in the community. This cross-continental bond is a reminder that the story of the African diaspora doesn’t end in suffering. It continues through celebration, resistance, and return.

The Brazilian Quarter is a living archive, a cultural landmark, and a symbol of resilience. It shows us that even when a people are scattered and oppressed, they can return, rebuild, and rise together.

In a world that often encourages division, this small part of Lagos stands as a reminder of what unity, pride, and heritage can achieve.

To preserve culture is to honour the past, protect the present, and empower the future.