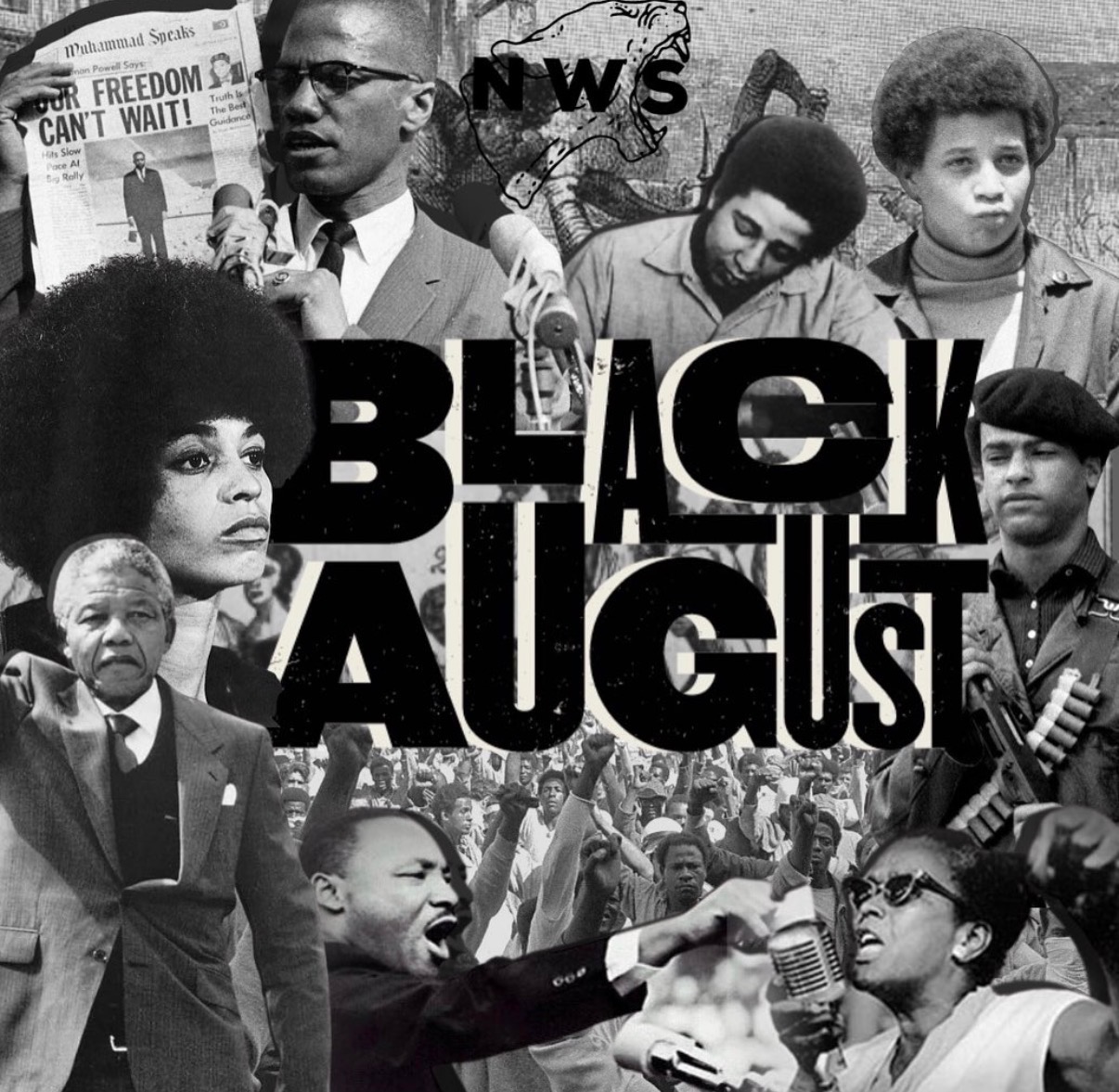

Every year, as summer peaks in August, Black communities around the world observe Black August, a month-long reflection on Black resistance, revolution, and the enduring fight for liberation. Unlike festive celebrations, Black August is solemn and purposeful: it began in the late 1970s among Black activists and prisoners in California, intended as a time to honour fallen freedom fighters and political prisoners and to educate communities about the long history of Black rebellion

The aim is to channel the spirit of past revolutionaries – to learn from their struggles and carry on their legacy. Black August reminds us that the story of Black liberation is not confined to one country or one era, but is truly global and continuous.

Why August?

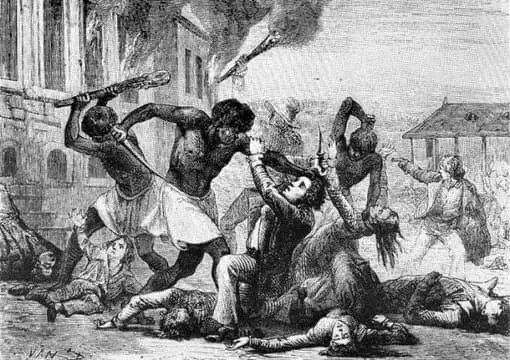

August holds a special place in Black history. The saying goes that “the month of August bursts at the seams with histories of Black resistance”. Indeed, many pivotal Black uprisings and milestones occurred in August. To name a few: the Haitian Revolution ignited on 21 August 1791, when enslaved Africans in Haiti (then Saint-Domingue) revolted against French colonial rule. This uprising grew into a 13-year revolutionary war that abolished slavery and led to Haiti’s independence as the first Black republic in 1804. Haiti’s victory – the only successful slave revolt in modern history – sent shockwaves through the colonial world. It proved that enslaved Black people could defeat empires, inspiring hope and fear in equal measure.

Fast forward to August 1955 in the United States: the brutal racist murder of Emmett Till on August 28, 1955, galvanised the civil rights movement. August 1965 saw the Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles, a fiery protest against police brutality and injustice.

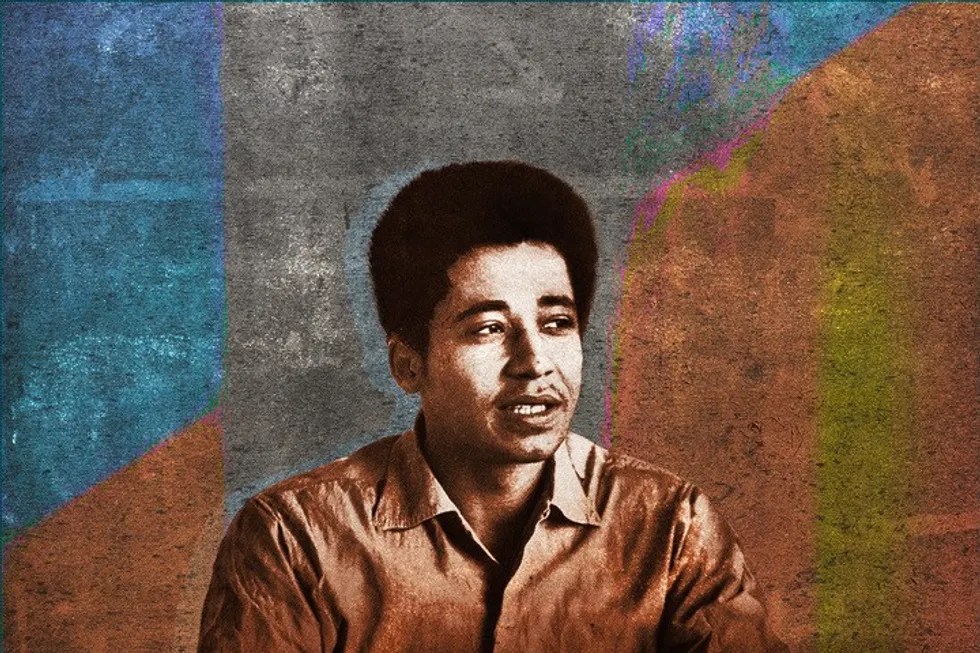

Even Black August itself was inspired by events in August, notably the prison rebellion led by George Jackson, a Black Panther, which culminated in his assassination on 21 August 1971. August, therefore, is a month of martyrs and milestones on the long road to freedom.

By dedicating this month to reflection, Black August connects the dots between these events, asserting that they form part of an “unbroken line of resistance and sacrifice” in Black history.

Global Black Resistance: Beyond Borders.

A core principle of Black August is to study Black resistance throughout the diaspora. This means looking beyond our local or national history and understanding that Black people’s struggle against oppression has been worldwide. For Black British communities, educators and Black youth in particular; this global perspective is powerful and affirming. It teaches that our ancestors did not endure brutality passively; time and again, they fought back and reshaped history.

For instance, consider the Baptist War of 1831 in Jamaica. Enslaved Africans, led by preacher Samuel Sharpe, organised a general strike and uprising demanding freedom. It became the largest slave rebellion in the British Caribbean, involving some 60,000 people.

Though the colonial forces brutally crushed the revolt and executed hundreds, the rebels achieved something monumental: their resistance accelerated the abolition of slavery. British authorities, shaken by the scale of the uprising, passed legislation to emancipate enslaved people across the Empire just a few years later, by 1838. In other words, enslaved Black Jamaicans were not passive beneficiaries of abolition – they were agents of their own liberation, forcing the issue through direct action. This is a crucial lesson for young people: our freedom was hard-won by our own people’s courage.

Travel to the African continent and you’ll find similar stories.

In Kenya, the 1950s Mau Mau rebellion saw forest fighters and villagers resist British colonialism in a quest to reclaim their land and rights. The British authorities responded with mass detention camps and violence, but could not extinguish the thirst for freedom. The uprising is widely seen as a key stepping stone to Kenya’s independence in 1963.

In Ethiopia, in 1896, the Battle of Adwa became a legendary example of Black resistance: Ethiopian forces, under Emperor Menelik II, defeated an invading Italian army, ensuring that Ethiopia remained independent. This victory was celebrated across Africa and the Black world. Finally, a non-European nation had halted the juggernaut of colonial conquest. It gave hope to anti-colonial movements everywhere.

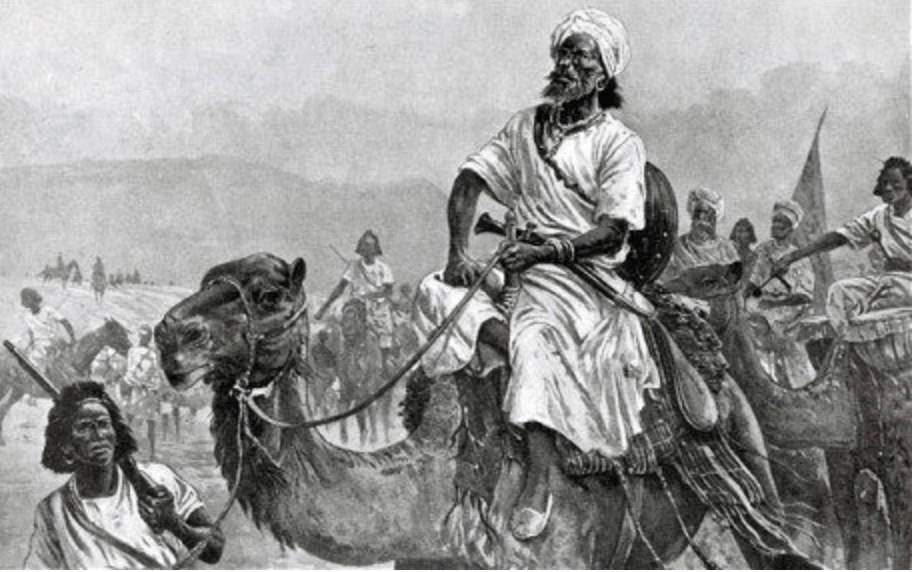

In Somalia, between 1899 and 1920, Mohammed Abdullah Hassan’s Dervish movement waged one of the longest anti-colonial wars in African history. For 21 years, Hassan’s guerrilla fighters defied the British and Italians, establishing a Dervish state in the process, until the resistance was put down by force. Such episodes, often left out of mainstream narratives, show that Black resistance was not rare – it was constant.

Why Teaching This Matters

For Black youth, learning about global resistance is empowering. It counters the Eurocentric narrative that paints colonised or enslaved people as victims who waited to be “saved” by others. Instead, these stories centre Black heroes: men and women who organised secret meetings, risked their lives, and sometimes paid the ultimate price to challenge injustice.

This fosters a sense of pride and possibility. If Dessalines, Sharpe, Nanny of the Maroons, Dedan Kimathi, or the countless unnamed fighters could stand up in their time, what can we do in ours?

It also nurtures solidarity. Black people’s struggles, whether in America, the Caribbean, Africa, or Europe, have common threads. Recognising this shared history of resistance helps build a sense of global Black unity. A Black British teenager tracing the story of the Haitian Revolution, or a Black American student learning about the Mau Mau, may see reflections of their own community’s struggles and victories. It’s a reminder that we are part of a bigger family and a continuous fight.

Teaching global Black resistance injects a radical awareness into education. It encourages young people to question why these histories were marginalised in the first place.

Why did we hear so little about the Haitian Revolution in school?

Why do mainstream history books gloss over colonial crimes and the rebellions against them?

Such critical questioning is itself an act of resistance against a curriculum that often sanitises or omits Black agency.

In the UK, Black history is often reduced to a few figures or the narrative of abolition led by white saviours, so incorporating global Black resistance into education is a radical act of truth-telling. It tells young Black Brits that their heritage is not just one of oppression, but also of heroism and innovation in fighting oppression. It’s an heritage that links them to freedom fighters in Jamaica, revolutionaries in Haiti, anti-colonial warriors in Africa, and civil rights activists in America. This knowledge can inspire confidence and a deeper understanding of identity.