By Serena

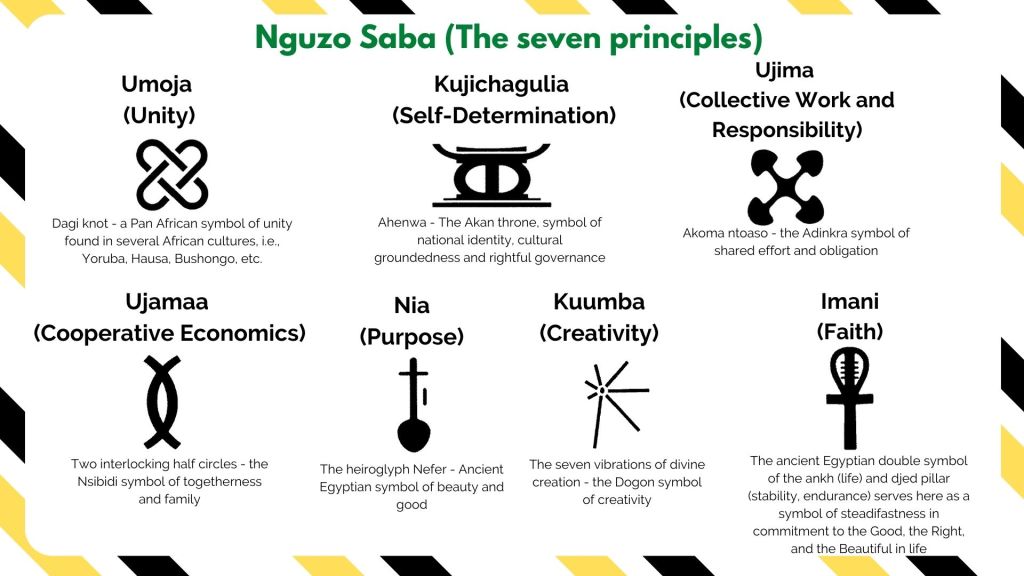

History of African hair + Significance

Throughout shifts in history, Black hair has been twisted and muted in a variety of ways. Yet it still represents one of the strongest connections to our traditions. And the modern styling of our hair is often the closest many will get to being able to practise their heritage since so much of Black history has been stripped from general history. Historically early African cultures used hairstyles as a form of identification. Allowing hair to communicate information such as family relations, tribe and social status without a word ever being spoken (BBC). During slavery, while being taken from their countries, enslaved Africans were also forced to have their heads shaved as a method of humiliation and ‘sanitation’ by white slave traders. This practice not only had roots in humiliation as European colonisers understood the significance of the intricate hairstyles often worn by African people but also a method of cultural eradication as sales would no longer have the ability to be identified through their hair as they had previously done. For slaves who were able to keep their hair, the lack of tools and time often left them unable to properly care for their hair. The intricate hairstyles they had previously worn with pride became a thing of the past and changed to simple styles and headwraps for convenience. As time moved on the policing of Black hair did not stop and conformity became the goal to fit into a world not made for them. During the civil rights movement Black hair took back its ability to communicate as Black people began wearing their hair out openly as a sign of pride during Black powers ‘Black is beautiful’ campaign as natural Black hair being worn out became a symbol of pride, solidarity and love for the Black community.

Modern Significance of Black hair + Self-expression

In addition to the Historical significance of Black hair, it also holds a modern significance as the meaning and presentation of Black hair. On the coattails of slavery and freedom movements, conformity became the norm with the introduction of products such as relaxers and the integration of Hot Combs Black women in particular took to straightening their hair to distance themselves from their Blackness to become more palatable to white people. This conformity was to survive in a world that still saw Black people as lesser which grew the stereotype that natural Black hair was not beautiful nor was it professional. This perspective on Black hair style exists today as within society Black hair is often seen as messy leading many to try and alter their natural curls to adhere to white beauty standards. And in the professional world whether it be through dress codes in offices or rulebooks in sports that have penalised Black people for wearing their natural hair (CBC). Black hair has also become a form of reconnection for many as more people start to accept and embraced Black hair Black people have started to find beauty in their Blackness and their natural curls

Why this ban is a violation

With the embrace of natural hair styling among the Black community many schools have taken the approach to further penalise Black pupils by banning certain hairstyles from school. These bans target hairstyles such as Afros, cornrows and braids worn by Black students through uniform and appearance policies (the guardian). These bans not only limit the types of styling that Black students can also further criminalise Black students as through these policies Black hairstyles are subconsciously categorised as bad, unprofessional and not acceptable for school further putting Black students at a disadvantage. Schools have been warned that such bans would violate EHRC guidance which states that such bans would “Discriminating against pupils about or because of their hair may hurt pupils’ mental health and wellbeing.”(The Guardian). In addition, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) said policies which ban certain hairstyles without making exceptions on racial grounds “are likely to be unlawful” due to their discriminatory nature. The Equality Act of 2010 also protects race and for a school to ban certain hair or hairstyles that are connected to their race and/or ethnicity would be discrimination under the act further making the action of these schools to ban these hairstyles illegal (EHRC).

Effect of the ban and harm it can cause

This ban on certain Black hairstyles also has a more individual impact as both the self-esteem and physical and mental health of Black pupils could be affected. The EHRC mentioned in their report that such bans could have a direct effect on the mental health and well-being of students as can be imagined when an inherent piece of your body is criminalised or banned from being in its natural state the mental ramifications especially on young pupils could be detrimental as they could find themselves struggling with accepting their natural beauty as their school’s policies force them to view their hair in a negative light. Furthermore, the banning of Black hairstyles would leave students to conform to white hair standards which would be viewed as acceptable under school policy. This could lead to students being forced to use methods of hair straightening or other styling that could cause irreversible damage to their natural hair. These treatments and the effort to find acceptable hairstyles that fall within these policy parameters can also place a financial burden upon Black families as by removing options such as afros or box braids parents and students may be faced with the financial burden of going outside of accessible hairstyles too and pay the price for more expensive treatment to fit the policy. In all, as stated in an article written by Remi Joseph-Salisbury and Laura Connelly, control over Black hair is a social control over the Black body which disadvantages Black students and which perpetuates the narrative that Black hair is messy and antithetical (Salisbury& Connelly).

Resources

- Resource: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-31438273

- Resource: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC-a787a8380

- https://halocollective.co.uk/halo-background/

- https://www.kikacurls.com/blogs/kikas-blog/natural-hair-the-history-before-the-movement

- Resource:https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/tangled-roots-decoding-the-history-of-black-hair-1.5891778

- https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/our-work/news/britain%E2%80%99s-equality-watchdog-takes-action-prevent-hair-discrimination-schools

- Resources: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/schools-afro-black-hair-human-rights-commission-rules-b1035552.html

- Resources: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/oct/27/schools-in-great-britain-warned-not-to-ban-minority-pupils-hair-styles

- https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/7/11/219

- Resource: How the ban continues white supremacy:‘If Your Hair Is Relaxed, White People Are Relaxed. If Your Hair Is Nappy, They’re Not Happy’: Black Hair as a Site of ‘Post-Racial’ Social Control in English Schools

- Resources: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-england-44521629

- Resource: https://www.centerforjusticeresearch.org/blog/im-not-my-hair-the-criminalization-of-black-hair