By Pamilerin Thompson

“I just knew there was stories I wanted to tell.”

Octavia Butler

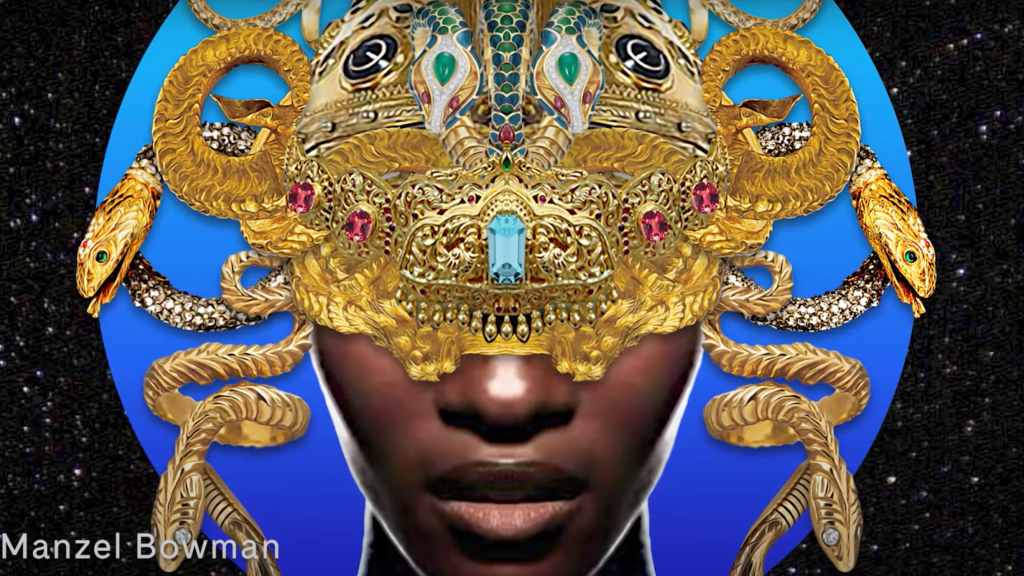

Afrofuturism is represented and presented over several mediums ranging from art, music, literature, film, design, fashion, and more. Most commonly, though, it is recognised in the science fiction novels by Octavia Butler, the jazz music of Sun Ra, and the eclectic and energetic beats of the ArchAndroid that is Janelle Monáe.

Recently, Apple commemorated Black History Month in the US with an ‘Afrofuturism’ Apple Watch band. But what exactly is Afrofuturism? How is it defined? How is it understood? What does it mean for imaginations of Black liberation?

For BLAM UK, Afrofuturism is the audacity, tenacity, and strength to reimagine alternative futures; therefore, in some ways, we are all living proof of Afrofuturism in action.

Afrofuturism was coined by Mark Dery in 1993/4, a white American author, lecturer, and cultural critic. This has been highlighted as problematic as the framing and understanding of the concept could favour and centre whiteness even in visions of a Black future. Nevertheless, Afrofuturism conceptually has been around long before Dery put a term to the idea and concept. The idea and ethos of what Afrofuturism is have existed for centuries in the minds of enslaved Africans who hoped, imagined, prayed, and resisted for their freedom from oppressive enslavers and the ideology that one day their children and loved ones would live in a world different from theirs.

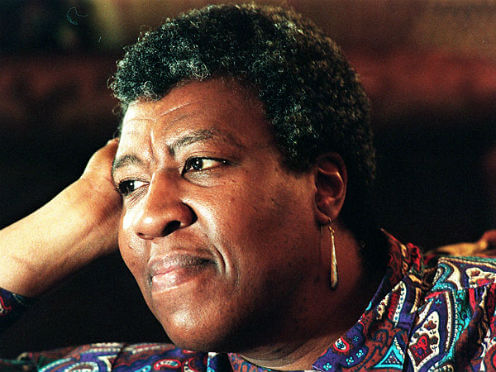

Octavia E. Butler & New School Afrofuturism Writers

Afrofuturism has a massive influence on science fiction that celebrates Black lives and Black stories. Afrofuturistic novels often depict fictional worlds set in different galaxies or dystopian societies filled with tales of moons and starry nights. It is interesting to see the way writers expand and use history to create versions of different futuristic events and alternative journeys taken.

Octavia E. Butler was a renowned African American author who received a MacArthur “Genius” Grant and PEN West Lifetime Achievement Award for her body of work. Born in Pasadena in 1947, she was raised by her mother and her grandmother. She was the author of several award-winning novels including Parable Of The Sower (1993), which was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and Parable Of The Talents (1995) winner of the Nebula Award for the best science fiction novel published that year. She was acclaimed for her lean prose, strong protagonists, and social observations in stories that range from the distant past to the far future.

Though the MacArthur Grant made life easier in later years, Butler struggled for decades when her dystopian novels exploring themes of Black injustice, global warming, women’s rights, and political disparity were heavily critiqued by a white and male science-fiction mainstream that Butler disrupted and re-shaped to give space to stories that Black individuals and girls could relate and engage with.

During her early years before her talent was more widely recognised Butler, always an early riser, woke at 2 a.m. every day to write, and then went to work as a telemarketer, potato chip inspector, and dishwasher, among other things!

Noughts & Crosses by Black British writer Malorie Blackman is an example of more contemporary young adult fiction of an imagined society, in which the novel’s reality differs from the reality of our own world. You can see the resemblance of modern society with a major twist! It is looking at the world with a different past. Looking at Black suffering through an alternate Blackman allows readers to imagine Blackness devoid of the white gaze. This is done by creating a past where colonisation and the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade never took place thus allowing Africa to grow into a wealthy and prosperous nation –– we begin to understand and see the impacts and legacies of the histories and experiences of our Black history can have. The novel pushes us to understand that what is normalised and mainstream stems not from a place where it is inherent, but from social norms and standards that have been shaped and set down by white supremacy. Blackman uses a love story to highlight the fact that structures and institutions created and upheld by people are the reasons that the impacts of anti-Blackness, capitalism, and empire continue to create and reinforce issues ranging from poverty to over-policing.

Afrofuturism imagines a future without white supremacist thought and structures that aim to violently oppress Black people and our community. Afrofuturism pushes and asks us to imagine (and develop) a liberated future where we are free to be our most authentic selves, celebrate our culture, and be well-versed in the tools and knowledge.

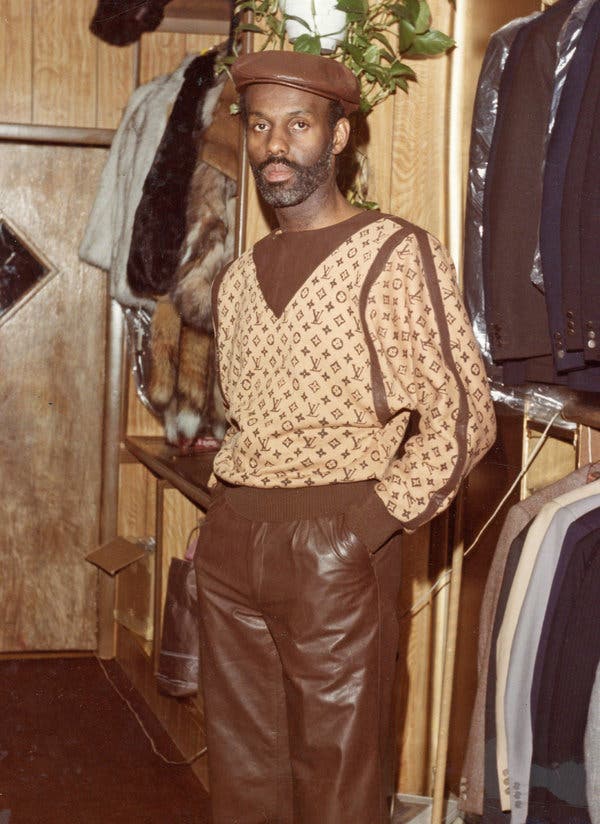

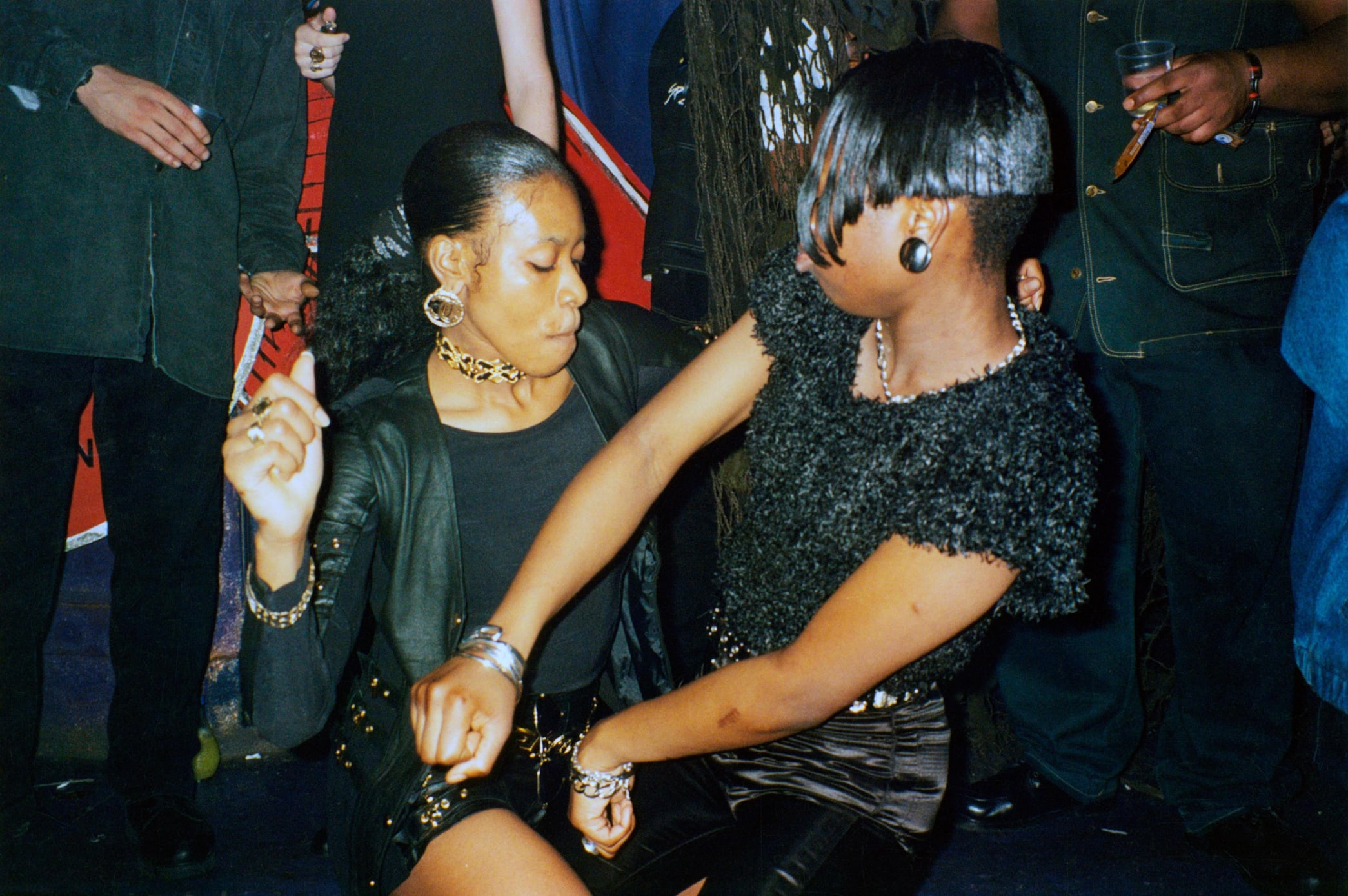

Afro-Fashion of the Future

Hollywood costume design institution, Ruth E. Carter, the first African American woman to receive an Academy Award for best costume design in 2019 uses fashion and costume design to shape and redesign the high quality and standard of design while emphasising the beauty in telling a story through the history and culture of fashion and style.

Carter has been a longstanding costume designer for A-List Hollywood films. She was the designer on Malcolm X, She’s Gotta Have It, and Selma! Carter attributes her success to the process by which she develops her designs. An important part of her design process is to ensure that the costume fits the actor who is wearing it so that the actor wears the costume and the costume does not wear the actor ‘you wear the costume, the costume should not wear you’. With over 40 films to her credit, this Oscar-winning costume designer gives us further insight in the docuseries ‘Abstract, the Art of Design’. In the series, Carter highlights the importance of ensuring that the fashion of Wakanda represented Africa authentically to show a fashion reality that had been unaffected by Western and Eurocentric ideals of beauty and style and proximity to whiteness.

Lisa Folawiyo also represents Afrofuturism in her fashion design work. Her designs have been worn by the Hollywood elite such as actress Lupita Nyongo and music artist Solange Knowles.

Upcoming Afro-futuristic designers are also gaining popularity outside of Africa and bring an energetic and creative zeal to the look. Out of Brazzaville is the Afrofuturstic work of Congolese designer Liputa Swagga. These designs often incorporate modern style with a nod to our global Black history and African past and contemporary African cultures. Dakar Fashion Week is the African continent’s longest-running fashion exhibition. It is the place for African designers to celebrate and showcase their work and talent and is the place to see Afrofuturistic fashion in its full flare and glory.

Africanising the Landscape & Architecture

Afrofuturism can also be seen and represented in the structures of buildings and a reimagining of landscapes.

Ekow Nimako uses only black pieces of Lego bricks to develop intricate and elaborate structures and sculptors to celebrate Blackness and futuristic depictions of African histories.

Hannah Beachler, a production designer, brought the scenes of Wakanda to life from the comic book to the silver screen by visiting and incorporating the culture and architectural history of countries in Africa. Beachler created the ‘Wakanda Bible’ which was a massive text that contained details of the people, the history, and the architecture of Wakanda.

In Nigeria, the concept of a floating school was cultivated by Kunlé Adeyemi a protégé of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). In 2013 he completed the award-winning Makoko Floating School. The building was constructed to provide teaching facilities for the slum district of Makoko, a former fishing village on Lagos Lagoon where over 100,000 people live in houses on stilts. It was designed as a prototype for African regions that have little or no permanent infrastructure, thanks to unpredictable water levels that cause regular flooding.

Sing a Freedom Song

Afrofuturism is a fluid ideology shaped by generations of artists, musicians, scholars, and activists whose aim is to reconstruct ‘Blackness’ in our cultural dialogue. Afrofuturism is reflected in the life and works of people such as Sojourner Truth and Janelle Monáe. Afrofuturism is a cultural blueprint we can use to guide society and creatively explore our community.

‘Ain’t I A Women’, by Sojourner Truth is a speech, delivered extemporaneously, by Sojourner Truth, who was born into slavery in New York. Sometime after gaining her freedom in 1827, she became a well-known anti-slavery speaker. Sojourner Truth’s ‘Ain’t I A Woman’ speech at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, is an example of Afrofuturism in action throughout history. In her speech, Truth is speaking out for the rights of Black American women during and after the American Civil War. Sojourner Truth calls on white women to reinforce a new way of thinking about Black womanhood and change the way they as white women relate to womanhood. Her speech pushes firmly back on the dominant cultural narrative and urges the audience to reimagine a future that confronts the historic devaluing of Black women.

Another historical example of Afrofuturism in music is chants and songs that inspired action against racism and violence and recognised that there was a future where enslaved Africans and African Americans would be liberated and find peace, rest, and tranquillity. Some examples of this are songs by Sam Cooke, ‘The Struggle’ by James Baldwin, ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’ by Gill Scott-Heron, and the bulk of the African American spirituals genre.

The Afrofuturist envisions a society free from oppression in following this thought process many aspects of the Black existence and struggle embody the Afrofuturistic vision.

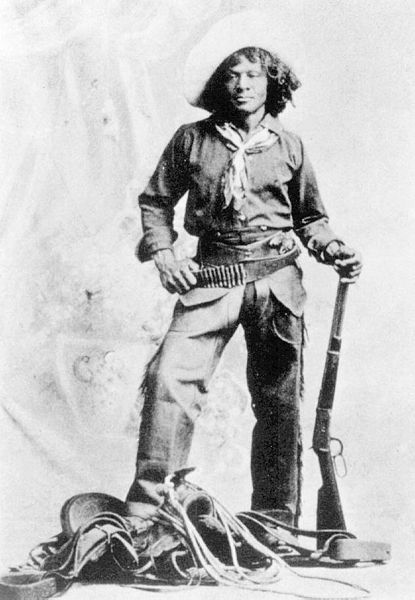

Radical Black Freedom Fighters

What does Afrofuturism mean for the imagination of Black liberation?

Radical social movements and freedom fighters like Assata Shakur, Fred Hampton, Huey P. Newton, Olive Morris, and Olusola Oyeleye are also Afrofuturists as they had the audacity, tenacity, and strength to reimagine better and more just futures for our community.

Afrofuturism in art has constantly used creativity and imagination to imagine a better future for our community. These images and creative stories offer us insight and solutions for change by offering us a radical basis for change and new ideologies that can spark revolutionary movements. As we go through aspects of Afrofuturism feel free to further explore writers and other artists and designers.

Afrofuturism is represented through the amazing work of artists, designers, and writers. The central figure to contemporary Afrofuturism is Janelle Monáe and you can see this in her music documentary, an ‘Emotion Picture’, titled Dirty Computer which deals with the politics of the state and robo-police pulling over cars filled with Black women. Afrofuturism has existed for centuries and is closely tied to the efforts and aspirations for Black liberation across the globe.

If you are looking to begin your reading of Afrofuturistic work, check out the list below:

Biniti: The Complete Triology by Nnedi Okorafor

The adventures of Binti first of the Himba people to attend Oozma University.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf (Book 1) by Marlon James

A Tracker joins a search for a mysterious boy who disappeared three years before but is targeted by deadly creatures.

The Deep by Rivers Solomon

The historian of the water-dwelling descendants of pregnant African slaves thrown overboard by slavers keeps all the memories of her people both painful and miraculous until she discovers that their future lies in returning to the past.

The Fifth Season (Book 1) by N.K. Jemisin

Vengeful Essun pursues her husband who killed their son and took him across a dangerous landscape.

The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead

Lila Mae, a Black female elevator inspector, must prove that her method of inspection by intuition, as opposed to visual observation, is not at fault when an elevator in a new city building crashes.

Minion: A Vampire Huntress Legend by L.A. Banks

Damali Richards must discover who is behind the brutal murders that have stunned the police and her.

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

An eighteen-year-old African American woman inherits a trait that causes her to feel others’ pain as well as her own, flees northward from her small community and its desperate savages.

Rosewater (The Wormwood Trilogy Series Book 1) by Tade Thompson

When something begins killing off others like himself, Kaaro, a government agent, must search for an answer.